Wavelengths (From the Web)

Wavelengths (From the Web)

Infrared is... This is hard to explain to someone who doesn’t have a scientific or technical background. We all know that light comes in colors? And that one of the ways of thinking about light is to consider it a wave? And, that just as a shorter or longer wavelength of sound results in a different musical note, a shorter or longer wavelength of light results in a different color?

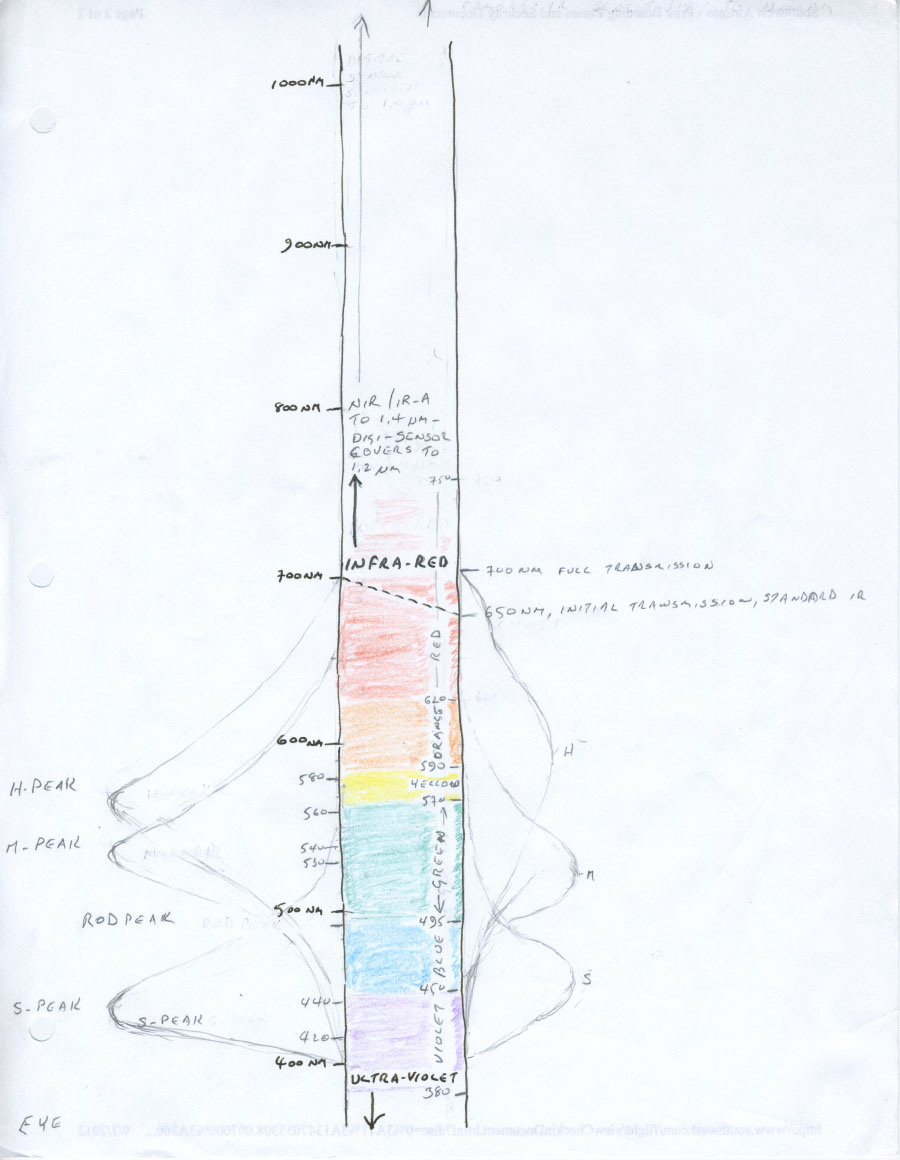

In fact, light consists of the same stuff (electro-magnetic radiation, or EMR) as x-rays and radio waves, and light is defined as the wavelengths of EMR that we can see with our human eyes, perhaps adding those wavelengths that are very close to the wavelengths we can actually see. So, infrared, or infrared light is the same stuff as red light, but with a longer wavelength than red and beyond the range of most human vision. Our eyes just aren't built to see it. When I first starting working in infrared I thought I’d better get a better grip on light as a thing, so I went online and read, found illustrations, and ended up drawing this little chart with my fountain pen and my niece’s colored pencils. The scale is in nano(billionth of)meters.

Laurence's Wavelength Study Drawing

The graph lines to the left show the sensitivity of the three primary color receptors in the eye, and the graph lines on the right the sensitivity of the three receptors of the camera sensor. If I were teaching formally I’d have to re-draw it because the left side, representing the human eye, is out of scale with the right side, representing the digital camera sensor. But, you’ll notice, the peaks are in roughly the same places. One of the lessons for me is that scores, hundreds, thousands of engineers and chemists have spent generations of effort building camera sensors to closely mimic the human eye. Of course! If you’re going to be creating something that needs to look natural, you’d copy the natural process, wouldn’t you? [1]

So, light as a thing: I do have an understanding of the physics of it, but I have to be honest and say that my grip on it is more or less at the high school level. On one side, and traditionally, we think of light and the rest of the EMR spectrum as waves, analogous to sound waves in the air. Those waves are fronts of higher or lower pressure in the gases that make up our atmosphere. A lot of effort in the last years of the nineteenth century went into trying to figure out what medium waves of EMR were waves in, and it turns out that they’re not really waves in anything. It also turns out that light is a thing [2] , and that there is such a thing as an actual light particle, called a photon, and it’s the physical act of these tiny objects hitting the cells in the back of your eye, the silver bromide crystal in the emulsion of traditional film, or the pixel of a camera sensor that makes the image. So, in some ways light is a wave, and in some ways light is a particle, and I, for one, am going to simply accept the duality of it. Partly because this level of understanding is enough for me as a practical photographer and partly because this is the level of understanding that is currently available. [3]

Infrared and Me: I first encountered infrared in a second hand encyclopedia my father bought me when I was eleven. Not in the science articles, but in the piece on Puerto Rico. I've no idea who the photographer was – the photos were attributed only to the Puerto Rico Board of Tourism – but they took pictures of entrancing clarity and originality using infrared film. I was permanently fascinated. As I started to get serious about photography myself I wanted to take pictures like that. But, as I learned, working with infrared film is very hard. The film is grainy, exposure is guesswork, and, to a lesser degree, focus is guesswork. Quality requires large format cameras using sheet film. All the more respect to the unknown Puerto Rican photographer! It was all too much for me, committed as I was to fast work in classic 35mm high speed film.

Digital changed the calculation... The sensors in digital cameras are inherently sensitive to infrared light – to avoid spoiling the visible colors infrared light is blocked from the sensor using an internal “heat filter”. That's a piece of glass that is opaque to the wavelengths of infrared light. Glibly put, all that is needed to take infrared photos is to remove the heat filter and replace it with a filter that blocks out visible light instead. In practice it requires a sophisticated technical lab with a clean room and high skills in disassembling and reassembling the camera. And for the Digital Single Lens Reflexes (DSLRs) that were the monarchs of my camera bag until quite recently, high skills in re-calibrating the autofocus function, since it's impossible to focus by eye, infrared being invisible! That's changed with my adoption of full frame mirrorles cameras since everything, focus, exposure control, viewfiding, and image capture, runs off of a single sensor. It remains exacting, and it's fairly expensive, but I've never regretted the cost. Another bonus of digital over film infrared is the fact that the native sharpness of the camera's sensor is maintained. One pixel in color converts to one pixel in infrared. My lab for the work has been LifePixel. I currently shoot infrared on a modified Canon R camera.

Footnotes:

[1] Digital mimicry of the human eye falls down in a couple of ways: One, the individual pixels on the camera sensor can only record one of the three colors humans and cameras use to record light. The cones that register color images in our eyes are also monochromatic, but they're very dense and randomly distributed. The grid of sensitive pixels on a camera sensor is a grid of squares, so, there is a patented pattern called a Bayer grid that emphasizes green (as the eye does, for other reasons) and the color value of a pixel is calculated from the pixel itself (recording one color) and the pixels surrounding it (recording other colors). Imperfect, but it’s good enough, and in today’s digital photography, very good indeed. Second, the response of the electronic pixel on the sensor to light is far more linear than the response of the chemical elements in your eye or the chemicals in old fashioned color film. I think this is much more visible than the Bayer issue. It can give a peculiar harshness to a digital photo, particularly in skin tones in people of European descent. It’s probably a big part of the reason that Hollywood is doing the needful to keep Eastman Kodak, the manufacturer of Glorious Eastmancolor negative film, in business. For me, digital good enough is good enough, and in fact amazingly good, but if you’re spending a hundred million dollars on making a movie and your return depends on how subtly attractive the actors are? You shoot Eastmancolor film, and the fact that there’s still a company capable of manufacturing film in the quantity and the quality needed means a lot you.

[2] I'm simplifying here, even, perhaps, by my own standards. I think a physicist would object to my calling a photon of light a thing or an object because it has no mass. Point taken, but it is an elementary particle and calling a particle a thing is about the level of precision this layman's brain can operate on.

[3] I did some extra reading on the history of physics while prepping this page, and ran across such concepts as the Ultraviolet Catastrophe and the Photon Antibunching Effect. This all sounds weird and funny, even ludicrous, to the layman. Easy to dismiss for some, but the real take away for me is that if you honestly want to fully understand this stuff you're going to have to commit – at a minimum – to an undergraduate degree in physics, and hard work while you're at school earning it.